“Let us march on ballot boxes until brotherhood becomes more than a meaningless word in an opening prayer, but the order of the day on every legislative agenda. Let us march on ballot boxes until all over Alabama, God’s children will be able to walk the earth in decency and honor.”

Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. said those words during his speech at Alabama’s State Capitol, after the Selma to Montgomery march had finished its five-day odyssey on foot down U.S. Route 80 – named Jefferson Davis Highway, to no one’s surprise – to demand equal voting rights for Blacks in the state.

Road sign for the Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail in Alabama.

Five days, on foot, sleeping out in fields overnight.

Now it’s the Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail, a designated All-American Road, and you can drive that same route today in a little less than an hour.

I wanted to spend a little more time than that, so after a conference in Birmingham, Alabama, I drove south and spent the night at the march’s starting point in sleepy Selma, at a downtown historic hotel right on the Alabama River.

The St. James Hotel is now a 55-room Hilton property, and it survived the Civil War’s Battle of Selma and Union forces who burned the town to cripple Selma’s Confederate munitions and weapons capability. The St. James was then called the Gee Hotel, owned by Confederate Major Gee but actually run by his enslaved helper Ben Sterling Turner.

After the war, the now-freed Ben ran local businesses and became a tax collector and a City Council member. All of that, of course, before Jim Crow laws and Klan terrorism destroyed those brief Reconstruction-era freedoms for Blacks, including voting rights. It took almost 100 years to get them back.

The hotel was pretty quiet when I was there, and the Sterling hotel restaurant was closed (although I was able to get a basic breakfast the next morning) but the highlights were a pretty center courtyard and the rear balcony, right outside my third floor room. I can’t imagine the post-COVID workforce challenges of trying to run a full-service hotel in a small agricultural town, to say nothing of dealing with the usual historic hotel maintenance issues, but I would absolutely stay here again.

Step out of your room onto the rear balcony of the St. James Hotel in Selma AL, and get this view of the infamous Edmund Pettus Bridge.

In early May the usual Southern bugs and mosquitoes weren’t too much of a problem yet, so I dawdled for awhile on that hotel balcony, which runs across the length of the building and is shared by multiple rooms.

It was rather disconcerting to be staying in a nice, modernized hotel, look down the river one way to see greenery and people recreating in boats, then look the other way and see the bridge that is named after a Confederate general and Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan.

The bridge that we all know from history as the site of Bloody Sunday.

View this post on Instagram

Bloody Sunday, which exposed white Alabama’s vicious resistance to voting rights and civil rights for all citizens, was the first of three attempts by marchers to show their determination at that bridge.

By that point, there had already been smaller rallies and voter registration marches to Selma’s Dallas County courthouse, Dr. King had been jailed in Selma (yes, there’s a “Letter From a Selma Jail” from him, which came after the more famous “Letter From a Birmingham Jail”) and a young man named Jimmie Lee Jackson had been fatally shot defending his grandfather during a night march nearby.

The historic riverside St. James Hotel, a Hilton Tapestry property in Selma.

But, why Selma? It’s not exactly a super-bustling town now, and it wasn’t in the 1960s, either.

I learned a lot about why by getting in my car after I checked out, and driving the short distance to Selma’s Brown Chapel AME (African Methodist Episcopal) Church, which was a key gathering place related to the voting marches.

Although Blacks made up about half of the county’s voting age population, only 156 of an eligible 15,000 Blacks were registered in 1961. The county even refused to turn over their registrar records to the U.S. Department of Justice, which was trying to challenge the situation.

The Brown Chapel AME Church in Selma AL, where Selma to Montgomery march participants gathered in their ongoing quest for voting rights.

As soon as you get to the church, you’ll see that it is located right in the middle of the George Washington Carver Home Projects, a housing complex built in the 1950s.

Related post – George Washington Carver’s birthplace and childhood home near Joplin, Missouri

As the historical marker below says, people who lived in these homes were not only some of the same people who marched and tried to register to vote, they also supported and hosted people like Dr. King and others who came to Selma to help that effort.

The Brown Chapel is to the left, and one of the Carver housing buildings is to the right. The church was literally in the middle of a good chunk of Selma’s Black homes.

In addition to the critical mass of affected and motivated people all located in this one area, and willing to support each other in trying to vote, there was also thuggish Dallas County sheriff Jim Clark and his deputies, who had a well-deserved reputation for harassing and abusing any Blacks who tried to register or help anyone else register.

Clark’s attacks on people started to get media coverage, to the extent that even the mayor began to worry about Selma’s “image” as a result. King and other organizers began to sense that Selma’s white terrorism structure, if exposed enough along with continued nonviolent protest, might result in a positive backlash in terms of national opinion and more Federal attention to voting rights in Alabama.

So, Selma became a focus of registration efforts.

Indeed, the television and media coverage plus national disgust that resulted from Clark’s troop attacks on marchers on Bloody Sunday were a turning point. Not only were marchers beaten and whipped and tear-gassed at the Edmund Pettus Bridge, they were chased from the bridge all the way back to Brown Chapel, where beatings continued including troopers on horseback riding up the very steps of the church.

It boggled my mind to stand before the church and imagine the terror. As Selma resident Joyce Parrish O’Neal says in this short video, Brown Chapel on that day was no longer a safe space. There was nowhere to escape this virulent white resistance to equal rights.

King then ordered and led a short demonstration march a few days later. In the face of a court injunction against marching, about 2,000 people walked to the Pettus Bridge, prayed, then turned back around on “Turnaround Tuesday.”

On the afternoon of March 21, 1965, after calls by President Johnson for a voting rights bill, and the lifting of the injunction against marching, AND after Johnson federalized Alabama National Guard troops plus sent other soldiers and Federal agents to the area to provide protection, over 3,000 people set out on the Selma to Montgomery march to demand voting rights at the Alabama State Capitol building in Montgomery.

The National Historic Trail’s interpretive center in Selma was closed for renovation during my visit, so I made sure to stop at the Lowndes Interpretive Center a little less than halfway through the drive.

The Trail was well-marked as I drove away from Selma, and even though the Lowndes facility is in “the middle of nowhere,” you can’t miss it.

Signage explaining the Selma to Montgomery march route, at the Lowndes Interpretive Center partway down the Historic Trail heritage highway.

The first night, the marchers camped on land owned by a Black farmer (anyone who supported the marchers was of course taking a tremendous risk of retaliation) and you’ll pass a marker about it before Lowndes. There’s not much to see there, and the campground sites are often on private property, too, so you don’t want to go tromping around on someone’s land.

There is a very good video to see at the Lowndes center, and the exhibits are well laid out.

1960s poster from the Southern Regional Council’s Voter Education Project.

One of the things that struck me was that in the 1960s, people tended to dress more formally, and many civil rights demonstrators made a special effort to dress nicely so that they would appear less threatening to the establishment.

Hats, gloves, church outfits, and nice shoes are not conducive to walking for miles on a highway in hot, sometimes rainy weather, though, and then sleeping on the ground at someone’s farm and eating volunteer-prepared meals served from new, clean garbage cans (a novel, thrifty way to transport and serve a lot of food.)

I don’t know how they managed it.

Another surprise for me was learning about Tent City, which was set up after the march on six acres off of that same Highway 80, by Lowndes County people and SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) volunteers.

It housed those tenant farmers and other people plus their families who were thrown out of their homes and jobs because they supported the marchers. You can step out of the Interpretive Center today and see the field next to the building where people lived.

Tenant farmer Blacks who dared to register to vote were often thrown out by white landowners, so Tent City was set up to house them.

People lived in Tent City for almost two years before they found new jobs and housing. They all shared one outhouse. If you’ve never seen a slop jar, there’s one in the exhibit so you can imagine doing your business in one, usually at night, without any privacy, in a tent.

Residents set up a loudspeaker and two-way radio because the only telephone was a party line inside a nearby farmer’s home.

Nevertheless, they persisted. “Now we could make a start for ourself” said one resident.

The Lowndes center works hard to personalize the Selma to Montgomery march and to show how it changed individual lives, in addition to newly-empowered collective actions like voting out the abusive Sheriff Clark about a year after the march.

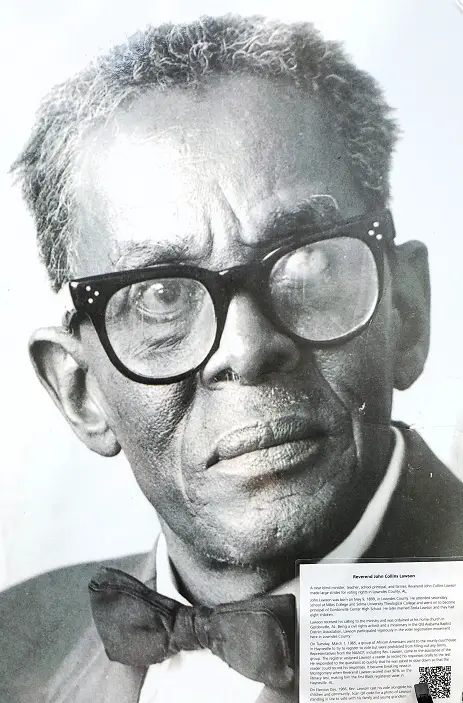

I was touched by this photo of an elderly, almost-blind gentleman named Reverend John Collins Lawson. Born in Lowndes County in 1899, he was active in the local NAACP in addition to his work as a pastor, school principal, and farmer. My goodness, what this man had seen in his lifetime.

Rev. Lawson, the first Black registered voter in Haynesville, Alabama, in 1965. Display at the Lowndes Interpretive Center.

There are plenty of mugs and stickers and other tchotchkes in the Lowndes Interpretive Center’s gift shop, but I truly appreciated their book selection.

I bought one called Southern Food and Civil Rights – Feeding the Revolution that I’m looking forward to reading.

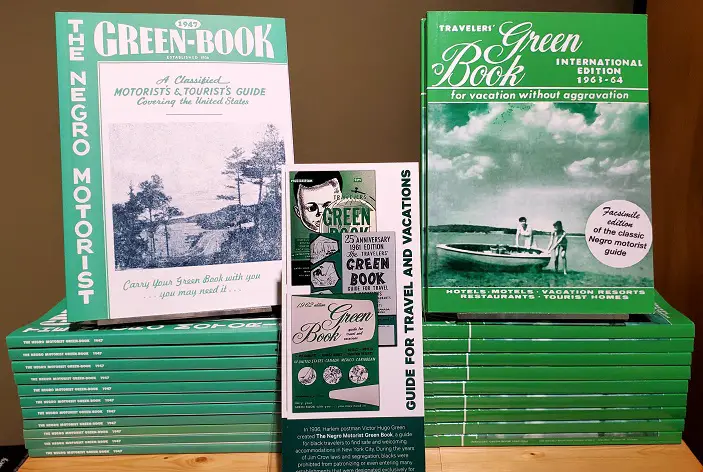

Another display caught my eye, too. I didn’t know that you can buy reproductions of the original Green Books, as described by Alison Stein, one of our former Perceptive Travel Blog writing team members. I’ve never forgotten her blog post for us about the books, and here they were in front of me.

I did flip one open to see what sort of Black-friendly lodging was available back then in the Austin, Texas area where I live. There were only a few private houses that had rooms to share, as I recall. How infuriating!

Where could traveling Blacks safely eat, get gas, and spend the night? The Green Book was their guide. Reproductions for sale at the Lowndes Interpretive Center.

This issue isn’t only an historical one, either.

There are plenty of places where Black travelers still don’t feel safe today, so websites and apps like Green Book Global not only have online communities where people can exchange information, they also work to highlight Black-owned businesses that travelers can support, similar to the EatOkra app that highlights Black-owned restaurants.

I left the Lowndes Interpretive Center even more conscious of how easy it was to drive down the highway compared to walking down it for five days, especially as I went past another campsite sign.

One of the campsite markers on the Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail.

The march ended with a crowd of around 25,000 people at the Capitol building in Montgomery, demanding change.

Even that joy and triumph was mixed with tragedy, as one of the marchers – Viola Liuzzo from Detroit – was murdered that very night by the Ku Klux Klan as she helped drive marchers back to Selma.

There is a memorial at her murder location, between Campsite 2 and Campsite 3.

Selma to Montgomery march participants and supporters at the Alabama State Capitol March 25, 1965 (courtesy AL Dept of Archives and History digital collection – click to see the original, including documentation)

When you finish the Trail in Montgomery, notice the brick church nearby.

That is MLK’s Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church, where he was instrumental in directing the 1956 Montgomery Bus Boycott. It also served as a staging and organizing spot when the Selma to Montgomery march ended at the Capitol steps.

For me, it was another tale of location, location, similar to the Brown Chapel’s location in the middle of a Black housing development in Selma.

You can practically throw a rock at the Alabama Capitol Building from that Dexter Avenue church. It was a seat of influence and power in the Alabama Black community, and it must have been quite threatening to the white establishment to have that church located right there near an Alabama state government that was determined to refuse civil rights to all citizens.

MLK’s Dexter Ave Baptist Church with the Alabama state capitol on the left just a block or two away, in Montgomery AL.

The thousands of people who came from all over to support and participate in the voting rights march were impressive in their dedication.

What touched me much more, though, were the very ordinary, often poor people from Selma and Dallas County who decided that no matter what happened, they’d had enough. They wanted to see the promise of American democracy fulfilled, and they refused to wait any more.

So they walked and walked and walked.

All photos and video by the author, except the one from the Alabama Dept of Archives and History

If you like this post, please consider subscribing to the blog via RSS feed or by email – the email signup link is toward the top of the right sidebar (or below each post on mobile). Thanks!

My family and I were in this very spot about a year ago. It was humbling to walk over that bridge in the footsteps of the people who marched that day in Selma and hear their story in the place where it happened. Thanks for the reminder of all I saw and learned there.

Thanks very much for your comment, Laura. I thought I knew a decent amount of history related to what happened in Selma, but I’d barely scratched the surface. I’m so glad I made this trip. It is indeed humbling.

I am glad you made that trip too, Sheila. As you mentioned Alison’s piece about The Green Book, I am thinking you might want to have a look at the book The Overground Railroad in which Candacy Taylor travels to many of the places referenced in Green Book editions over the years. It’s thoughtful history with memoir woven in. Here’s the story I wrote about that book with a bit more about it: https://perceptivetravel.com/blog/2022/05/17/overground-railroad/

Thanks, Kerry. Sundown towns along Route 66 certainly brings one up short, doesn’t it? I wonder if the upcoming Route 66 Centennial in 2026 will address that. It wasn’t the friendly “Mother Road” for everyone.