I visited The National Civil Rights Museum a few years ago, and one artifact that I saw on display has been lodged in my mind ever since: a guidebook for African Americans who were traveling through the segregated south.

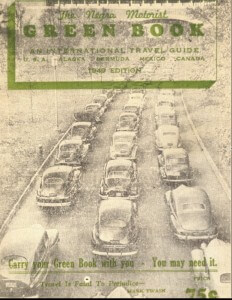

I don’t remember the name of the guidebook, and I could only see its cover — it was, as I recall, a black and white photo of an attractive African American woman in a trim early 1960s dress, posed in front of a car. I really wanted to get a look inside. I was never able to track that guidebook down, but I found a similar one: The Negro Motorist Green Book. It was published annually, starting in 1936. The 1949 edition cost 75 cents, and although it contained only 80 pages, had an international scope, covering the USA, Alaska, Canada, Mexico and Bermuda. The cover has a photo of cars on a road, huddled tight together, bringing to mind a funeral procession, an invasion – although it’s actually of New York City’s West Side Highway.

Travel’s “Difficulties and Embarrassments”

The Green Book was the project of Victor H. Green, himself an African American from New York. This wasn’t the first book of its kind (nor the last), but apparently the competition had gone out of print. The painful story of the trip (or trips) that inspired Mr. Green to put this book together isn’t told directly, although it is hinted at. “It has been our idea to give the Negro traveler information that will keep him from running into difficulties and embarrassments, and to make his trips more enjoyable.” Difficulties and embarrassments that could be encountered in hotels and in restaurants, at barber shops and drug stores, in night clubs and in taxis.

Similar clues are also encoded in the introduction by Wendell P. Alston, a special representative of the Esso Standard Oil company, who, he says, spends about half the year traveling on behalf of his employer. “For most travelers, whether they travel in modern high-speed motor cars, streamlined Diesel-powered trains, luxurious ocean liners or globe encircling planes, there are hotels of all size and classes, awaiting and competing for their patronage. Pleasure resorts in the mountains and at the sea shore beckon him. Roadside inns and cabins spot the highway and all are available if he has the price. For some travelers, however, the facilities of many of these places are not available, even though they may have the price…the Negro traveler’s inconveniences are many and they are increasing because today so many more are traveling…”

Alston lists several reasons why African Americans were traveling in such numbers: they were members of orchestras, attendees of concerts, touring clubs, students, teachers, and business men like himself, who were working for white-owned companies to expand their penetration into the African American market. In other words, The Green Book was directly aimed at a traveler who was trying simply to get on with whatever it was that had motivated their journey, and who did not wish to make a political point with their very presence.

Alston lists several reasons why African Americans were traveling in such numbers: they were members of orchestras, attendees of concerts, touring clubs, students, teachers, and business men like himself, who were working for white-owned companies to expand their penetration into the African American market. In other words, The Green Book was directly aimed at a traveler who was trying simply to get on with whatever it was that had motivated their journey, and who did not wish to make a political point with their very presence.

At the same time, a guide like this does play a role in propping up the segregated status quo – it’s easy for me to imagine that certain sponsors like Esso or Ford were willing to sponsor this guidebook not out of any great sense of enlightenment but because it would keep African Americans from wandering into white institutions by accident.

The publisher seemed to wrestle with the political implications of providing practical information to help people navigate a diseased system: the cover features the inspiring Mark Twain quotation “Travel is Fatal to Prejudice”, but only in smaller letters beneath a veiled warning about the dangers of being near prejudice when it is attacked: “Carry Your Green Book with You –- You Might Need It”. And the final paragraph of the introduction addresses the quandary squarely: “There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges within the United States. It will be a great day for us to suspend this publication for then we can go wherever we please, and without embarrassment.”

That day, sadly, was not very close at hand: I also found the twentieth anniversary issue of Green Book published in 1956, now renamed The Negro Traveler’s Green Book, to account for the popularity of air transportation. Its cover had shed both its inspiration and its warning, but gained a sketch of a traveling family that looks curiously white. The introduction again expresses hopes that the book will become obsolete eventually, but then concludes: “In looking ahead…a trip to the moon? Who knows? It may not be as improbable as it sounds. A New York scientist is already offering for sale pieces of real estate on the moon. When travel of this kind becomes available, you can be sure that your Green Book will have the recommended listings!”

It was meant as a light-hearted comment, but what a sadness at its heart: nearly 100 years after the Civil War had ended, it was hard to imagine that segregation would fail to penetrate every frontier, even the earth’s atmosphere, and wrap its tentacles around the moon.

To learn about a selection of other ways to explore African American stories, consider this post Black History: Seven Ways to Explore

Consider subscribing to our stories through e mail, and connecting with us through your favorite social networks. You will find links to do that in the sidebar — and while you’re at that social network exploring, we invite you to keep up with our adventures by liking the Perceptive Travel Facebook page.

Another good history lesson. And with 75% white population and 13% black, serves to let us know we have come a long way. Also serves to remind us we should be thankful that most blacks and whites want all types of crime to end.

But too many powerful and affluent, both blacks and whites, want crime to grow for profits. Billions in revenue to be had to provide products and services for criminals. Those evil groups, made up of blacks and whites, are the evil that serves to divide instead of unite blacks and whites. Done for greed, influence, power. Possible because we have so many poor, dumb, and needy because of the many and varied systems in place that enable criminal production. We, blacks and whites, allowed this. We are the enablers of the enablers of criminal production.

Let’s be even more thankful that 100% of blacks and whites do not become criminals. Consider if 100% of blacks and whites became criminals. With 75% white and 13% black population ratio, and both sides with no morals, it would be a very bad thing for blacks. It could become like things are in Africa today for many blacks. Where blacks kidnap, torture, kill, and enslave other blacks. Where a variation of “The Negro Motorists Handbook” black travel guide is still used to escape horrid abuse by blacks.

Actually we still have similar travel guides throughout the US. There are certain places blacks and whites just don’t go because of their race, or because of the level of crime regardless of your race, or because of gang warfare, or because of large communities of street dwellers.

Have a safe trip to the voting station.

Where can I purchase the negro green book travel guide

Reproduction editions of various years of The Green Book may be found at Bookshop.org and on Amazon, and perhaps through other booksellers as well.